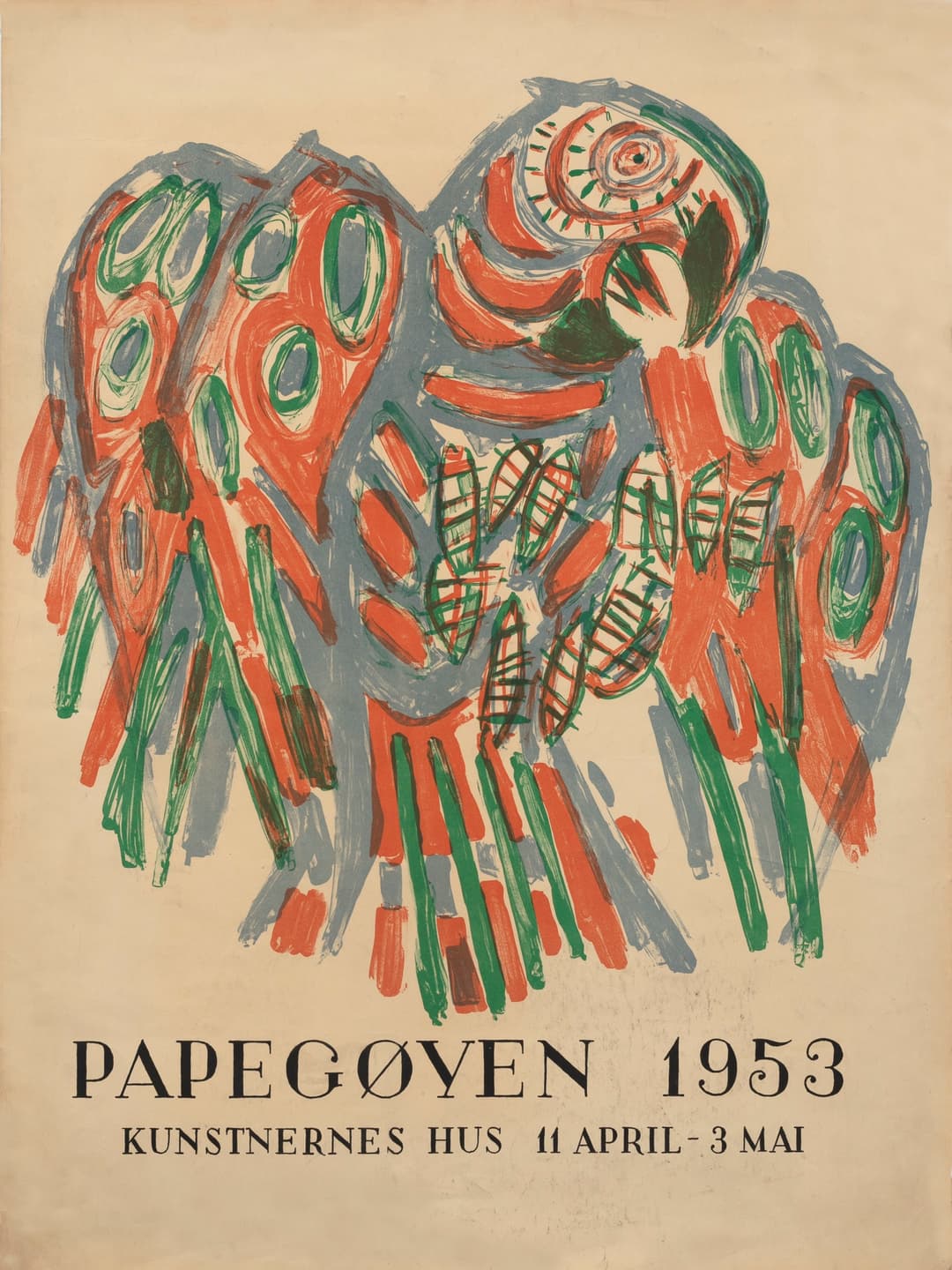

Parrot

Gunvor Advocaat, Oddvar Alstad, Herman Bendixen, Roy Blohm, Arne Bruland, Bjarne Brunsvik, Ludvig Eikaas, Gunnar S. Gundersen, Thore Heramb, Tore Haaland, Guy Krogh, J.F. Michelet, Olav Mosebekk, Knut Ruhmor, Atle Urdal, Jacob Weidemann og Egil Weiglin.

There is no solemn collective name they have chosen for these 17 painters. It sounds purely frivolous and it undoubtedly hides a touch of self-irony. But just call them parrots, they sure have enough confidence in themselves to handle it. And besides, the name has a positive connotation. Here there is a motley display of colour, youth, freedom and a reluctance towards conversion. A new generation is emerging.

They are probably not really revolutionary, do not break the mold of their older colleagues and do not preach any epoch-making artistic program. They respect what is good in other people's art and even use it, but they use it in their own way. After all, they add new elements and new values to our art that others will again make use of. Apparently, there is not much that binds these painters together. The difference between them is striking. Side by side we find realism and abstraction, sophistication and social pathos, decoration and philosophy. But of course there are reasons why they have applied together. One of them already lies in the fact that they are fairly the same age, that in other words they have many experiences in common - not just the purely artistic ones, not just the academy education in Oslo, but a network of events and phenomena of political, social and purely human species. Mostly, they were shaped as artists during and after the Second World War. Like the rest of us, they have felt the crushing weight of life and looked to the future in uncertainty and anxiety. Still, they have probably reacted to life in their own unique way, because they have experienced it with the open eyes and minds of artists.

One of the most striking things about the exhibition seems to be its emanation of courage and matter-of-fact optimism both when it comes to art and social conditions. Already in that it has something to give us. It also works convincingly because each of the painters has found or is in the process of finding the core of their personality. They will express the truth, their personal and well-founded point of view on life. And precisely by virtue of their honesty, they can perhaps strengthen our faith in the possibilities of the individual in the world collective we seem to have to conform to.

However, despite the exhibition's diversity, what gives it a homogenous character and thus impact are the purely artistic common features that bind the participants together. Above all, they all seem to have a need to define certain concepts and to visualize simple and solid human values. It is natural in a time that undeniably shows certain tendencies towards spiritual dissolution and this is expressed in a particular rigor in the artistic expression, a certain simplification and an absolute solidity in the design language. This tendency is perhaps most clearly expressed in the general desire for abstraction in the design language, the aim is to find concentrated, general and striking expressions. Some paint purely non-figurative, objectless pictures, some reduce the color scale to almost only white and gray and black. But if you look closer, you will find that the exhibition also provides space for the most meticulous realism and the greatest joy of storytelling. As unifying undercurrents run the joy of healthy artistic work, the dislike for insignificance, the urge for clarity. Therefore, the exhibition can give us contact with the most essential forms of human need for expression without ever seeming to encounter foreign elements.

We can take our starting point in Roy Blohm's factual and rigorous account of his world - the backstreets, everyday life, quiet working people - a world without external beauty, but made heartfelt by Blohm's understanding of and love for the distinctive and significant even in rather small and almost grotesque details. Guy Krogh has some of the same sense for the details of everyday life, but he certainly sees them in a different context and shows them to us in a different way. They become powerful points in an imaginative account of life, or purely picturesque jewelry in artistically well-calculated compositions. A larger and simpler, more tangible view of life is found in Bjarne Brunsvik and Herman Bendixen who, in their own way, seek to create a colouristic and decorative synthesis of the visual experiences, in simple large areas of color that already seem to be in the process of transitioning into abstraction. A similar tendency is represented by Gunvor Advocaat who, through painterly means, will recreate his encounters with things and figures, surface, form and space, but who, despite his authoritative grasp of the pictorial element, preserves the feeling for the essence and character of the subject. This is also how Olav Mosebekk operates with his close and everyday subjects at once as factors in a rich pictorial world of black, white and gray and as an expression of the most elementary and essential human emotions. A more ambitious will emerges in the pictures of Atle Urdal, which now seeks to realize itself in large figure compositions, where each part at once tells about reality and indicates a link in a constructive spatial structure. And then we encounter a growing will to make the whole image clear, coherent and effective.

With Egil Weiglin, the motifs can be the most unassuming and the color strong and lush, but the richness of his small compositions is contained within a separate heavy constructive unit and the details come together as concentrated and far-reaching declarations of love. Thore Heramb goes even further. With him, things are simplified almost into formulas, into the very simplest and thus most significant symbols of the realities he has become concerned with, and at the same time into usable elements in rich pictorial compositions.

With Joh. Fr. Michelet, we take another step further. Admittedly, his pictures still contain recognizable elements, the sources of inspiration may be clear, but these elements have been abstracted into almost geometric figures, transformed into links in a dynamic and powerfully colorful world of form. And then we meet with Gunnar S. Gundersen the purely Norwegian figurative painting, where the pictorial elements are no longer symbols of the visible realities, at the height of emotions, but where they nevertheless gather into a world that has surface and spatial extent and where everything is in motion. Ludvig Eikaas takes a similar position, but his ascetic coloring also contains an almost mystical lyricism which again seems to bring us back to reality.

With Knut Rumohr, this lyric has become a violent emotional expansion. His violently moved non-figurative compositions live an enigmatic life, filled with conflicts and battles which in turn lead us into the very real existence. And thus we approach the last phalanx of painters at the exhibition. Jacob Weidemann moves in his pictures on the borderland between dream and reality, between abstraction and reality. Arne Bruland seeks from strict abstraction towards a freer idiom that can serve to give his symbolic and socially emphasized figure compositions even stronger expressive power. Tore Haaland is in a similar transitional stage, as he seeks a clear form that can cover a strongly expressive colouring. In his later pictures, Oddvar Alstad wanted to find the most general expression of his sense of social justice in exceptionally strict and simple figure compositions. Thus we are once again back to the rigor, the will to fight for the impactful matter-of-factness in the expression that most cleanly and clearly allows each individual personality to manifest itself.

And then we'll see if anyone, after going through the exhibition, will really stick to an odious definition of the parrot name.

-Reidar Revold.