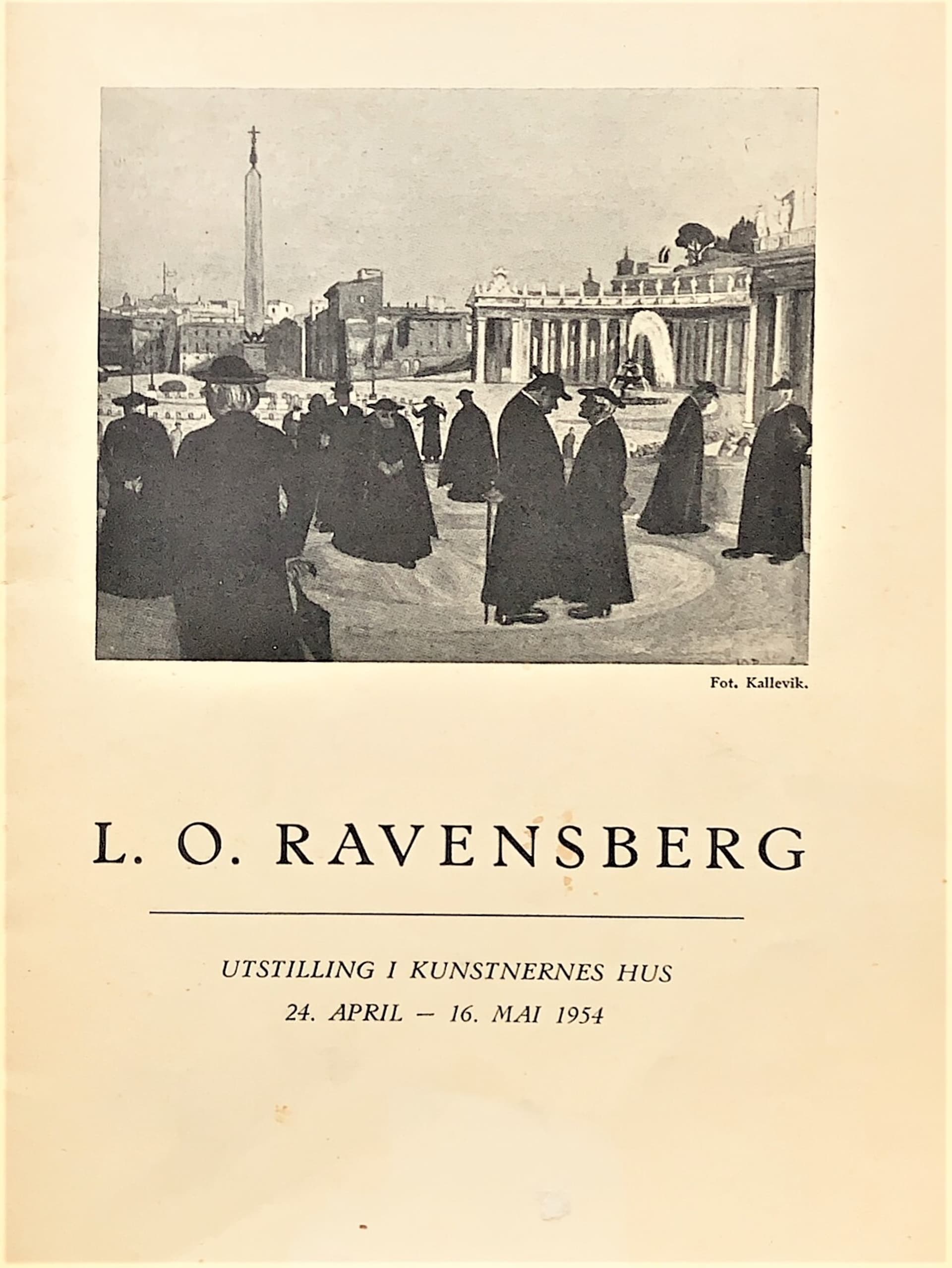

Hjalmar Haalke and L.O. Ravensberg

Retrospective exhibit

Hjalmar Haalke: Was born on 12 April 1894 in Trondheim. Began his training as a painter in 1915 with Eivind Nielsen at the School of Handicrafts and Arts and has since then lived in Oslo. Exhibited for the first time at the Autumn Exhibition in 1919 and has been an annual exhibitor since 1925. Traveled to Paris for the first time in 1922 and became a pupil of Araujo and during a number of stays there was a pupil of Bissiére, Waroquier, Dufresne, Per Krohg and Otte Sköld. 3 solo exhibitions at Kunstnernes Hus and 2 exhibitions at Blomquist. 1 Separate exhibition in Royal The Academy in Stockholm and a number of exhibitions in our art lectures around the country. Represented in the National Gallery (2) National Museum, Stockholm (1) and in most Norwegian art associations' permanent Galleries.

L. O. Ravensberg: The absolute honesty in the visual arts presents its practitioner with many problems that require both renunciation and a strong personal attitude to life in order to be able to solve them. The quite natural demand for beauty alone can often cover what is the core of art: the truth about oneself and one's experiences. It is one's personal property for all time, while beauty is very often a capricious daughter of the times who takes her cue from her lovers, sometimes foreign gods, sometimes cultivators of patriotic subjects such as: The national colour. In its artistic form, it can seem captivating in the moment, but very often lacks a personal content.

Of course, image making that has its noblest starting point in the desire for beauty can be excellent art, if it is based on a personal experience and when form and content complement each other in a fulfilling way, as for example in Torne's painting. Although he has received impulses from both Danish and French art, the beauty of his painting is exclusively marked and his own vision and reveals much of his own personality. Nevertheless, his art is severely limited and only expresses experiences within his own small world. It does not say anything about whether it characterizes the time and therefore also does not satisfy Christian Krohg's requirement: That it is the picture of the time that one should paint.

If, on the other hand, the artist seeks to penetrate to the truth of the experience he has encountered and portrays the impression it has made on him purely personally, the artistic form seen from an aesthetic point of view will very rarely seem flattering and many times offensive, but seen in conformity with the ethics of the content gives the image a condensed meaning, where a sense of complete coherence between form and content cannot be an optical illusion. It has a clearly formulated and open content that conveys the truth. It certainly makes great demands on the image's design, as form and content play an equally decisive role in a perfect interplay to give the work of art a fulfilling character that unmistakably reveals the artist and his recognition of the truth about his experience - and the demands increase with the artist's willingness to give a picture of the time and the impression it has made on him, because purely human considerations take precedence over demands for beauty of form.

This is the starting point for Ravensberg's artistic development. His aesthetic form, which has an almost foster-brotherly connection to the content he evokes in the work of art, is not based on any demand for external beauty, but is determined by an intrusive dialectical representation that is controlled by the truth that the ethical content of the content must convey about, and which the artist from a strong personal point of view seeks to reach. Such a search for truth must quite naturally be borne out of an outlook on life, and as my subject demands to be treated without any pretensions, it must be known: that Ravenberg's outlook on life is steep and environmentally determined and not a little aristocratic in spirit and yet free-spirited in relation to the civic spirit of 48. Hans artistic morality is more based on the logical than on the talented, and this has probably partly been the reason for his isolated position in Norwegian artistic life, where there was greater respect for talent than for discipline and tradition.

When Ravenberg's art finally found its rightful place around 1910, Norwegian painting was already well into the cultivation of beauty in the artistic form, where color in particular was of decisive importance, just as the content was characterized by the beautiful and intimate in the artists' own environment. To avoid getting lost in the art historical wilderness, we will content ourselves with mentioning Wold Torne, partly because his painting must probably be described as the strongest and clearest within his circle, and partly because he, only four years older than Ravenssberg , belonged to the same generation. It was this, the best-knit circle that became the determining factor in Norwegian art life and under the name "The Fourteen" at the 1914 Jubilee Exhibition received its baptism of fire and quite a few years later came to enjoy the special favor of the national gallery director — Wold Torne as Norway's Cezanne.

Although it has contributed to Ravensberg's reluctance to step out into the arena of art all alone, it has not been the deepest reason. Rather, it must be sought in his outlook on life and its rigid attitude, and not least in the spirit aristocratic in the person who did, that he felt himself standing aloof from the materialistic values of his profession and with a certain skepticism saw them being used as objects of speculation, not least during the the first world war.