British watercolors through 200 years

This exhibition has been organized at the initiative of the British Ambassador to Norway, Sir Michael Wright, and it has been organized by Thos. Agnew & Sons, London. We sincerely thank them for the opportunity they have thereby given us to get to know an important side of British art.- The Directorate of Kunstnernes Hus

Of the European schools of painting, the English one is the only one where watercolor painting has been considered equal to oil painting. In England it has been practiced by almost all the leading painters over the past 200 years. Not even the portrait painters have despised this technique, as we see it in the two surprisingly freely created drawings - portrait studies - by Romney at the exhibition. In fact, there are certain painters who have almost exclusively made watercolours, such as Alexander Cozens, J. R. Cozéns and Girtin who are thirty of the most original artists in the whole English school. Turner, who is arguably England's greatest painter, is also the greatest watercolourist and his production in this area is overwhelming. Paradoxically, it has been the main reason why he has continued to be underestimated outside of England, especially in France, where watercolor is considered only a description for amateurs. Nevertheless, Turner, with his rainbow palette, was a significant forerunner of Impressionism.

This exhibition cannot of course be completely representative, but its aim has been to show a selection of works by major and minor artists, sufficient to allow one to follow the development of watercolor painting from its first flowering around 1750 until today.

The school's beginnings in the early 18th century were modest enough. Then the watercolor was used mainly to color pen or pencil drawings with a completely topographical character, e.g. Bamfylde's drawing of St. Michael's mountain. Gradually the color and brushstrokes became freer, but many artists largely retained the topographical view, even when they added so much grace and skill to it as the brothers Thomas and Paul Sandby who both worked for King George III at Windsor. Richard Wilson went a step further. He drew two views near Rome when he visited there exactly two hundred years ago, and they are precise in their topographical account, but they are also full of the warm Italian light that inspired Wilson the rest of his Iiv.

However, it was with Alexander Cozens and his son John Robert that the technique was finally freed from the previous restrictions and conventions. Alexander Crozens who was born in Russia around 1717, settled in England in 1746 or shortly afterwards and became a drawing teacher at Eton College. He was an innovator in that he often used the brush without any previous drawing. It enabled him to sketch quickly and broadly, and in his hand the watercolor could capture the grandeur of the mountain landscape that moved him so strongly. His use of color was nevertheless severely limited, and he left this legacy to his son, whose earliest watercolors are almost monochrome. They were made during a trip he took to Switzerland and Italy in 1776 with his benefactor, the dilettante and connoisseur, Richard Payne Knight (Nos. 27 and 28). Later, during his second journey to the Continent, he reached the full expression of color, and his late water-colours, which have a tinge of the melancholy of the coming madness, are in their nature the finest things produced in the 18th century.

In addition to his direct influence, Cozens played another important role in the development of English watercolours, for his doctor Thomas Monro, who was a deep admirer of his work, used the young painters Turner and Girtin to copy so many of Cozens watercolors that ban could find. In their most 'receptive age' they became familiar with these wonderful watercolours, and one still notices echoes of Cozens in their works.

Girtin was originally apprenticed to Edward Dayes, an artist whose talent rarely reached beyond the charming, except for some architectural watercolors of which we have a good example in this exhibition. Turner was also apprenticed to an architectural draftsman, Thomas Malton. After this initial training and work for Dr. Monro, both Girtin and Turner developed rapidly, and it was with them that English watercolor painting found its final expression. It won from time to time until a lyrical beauty that can well be compared with the greatest in English poetry. Indeed, Girtin's relationship to the landscape is close to Wordsworth's. Girtin died in 1802, aged 27, and it was left to Turner to 'bring the watercolor to perfection. He introduced increasingly clearer and brighter colors and dissolved his entire subject in a bath of light, but nevertheless he never allowed his composition to become loose, which he probably owed in part to his earlier architectural drawing. Turner's sophistication is admirably demonstrated by the two works in the exhibition: from "Richmond Bridge" , which is still calm in color and conventional in outlook, to "An Alpine Stream" 35 years later, when Turner, to use Constable's expression, painted "in colored vapour".

Turner was a solitary meteor and few of his contemporaries or after: followers understood enough to want to follow in his footsteps. Girtin, on the other hand, had a profound effect on his followers and it is said that it was the encounter with Girtin's 30 watercolors in Sir George Beaumont's collection that made Constable become a painter. Undoubtedly, both he and Cotman were influenced by Girtin and this also applies to several less significant artists such as Eg. Varley. Despite their beauty, Constable's watercolours, however, must give way to his oil paintings, but Cotman is primarily a watercolor painter and his work with the form gave the technique a new strength. It formed an alternative to Turner's growing concentration on rendering atmospheric effects. The Girtin successor who took his innovations a step further was Peter de Wint. Not only was his brushwork freer and bolder than that of his predecessor, but his color was also wonderfully rich and warm. He could capture the color glow of the English summer with astonishing skill and spontaneity.

Alongside these great names there were also countless less significant men who painted English life and English landscape in a way that still delights us. Some of them, e.g. Rowlandson and Cox produced some works that are on a par with the best, but even the least known artists of this period are capable of rising above themselves at certain moments.

From Turner's death in 1851 until about 1900, English watercolor art was at its lowest ebb. Collectors wanted either falsely romantic landscape renderings or, later in the century, the prosaic reproduction of the tour. It killed art and brought happiness to artists such as Birket Foster and Leader. For this reason, the period is not represented in the exhibition.

English painting was revived at the end of the 19th century by two artists who were both born in 1860, Philip Wilson Steer and Richard Sickert. Both were influenced by Whistler — and Sickert also by Degas, as we can see from his work at the exhibition. They were leaders of the so-called English Impressionists and their contribution to English art has not least been to instill French Impressionism into an English tribe. Wilson Steer, with his transparent color and his skill in rendering a moving sky, is perhaps the greatest English landscape painter of this century. His watercolors make him a worthy bearer of the tradition of Cozens, Constable and Turner.

The exhibition ends with a group of 29 watercolors by 16 living artists. No purely abstract work has been selected, and the artists who have been invited to exhibit fall, with three exceptions, into two main groups. The first comprises those who belong to the mainstream of English watercolor art and who are Wilson Steer's natural successors. This group is led by Connard, Steer's successor and friend, and continues through Pitchforth, Dring, Darwin and Mary Potter to Leslie Worth, the youngest artist represented.

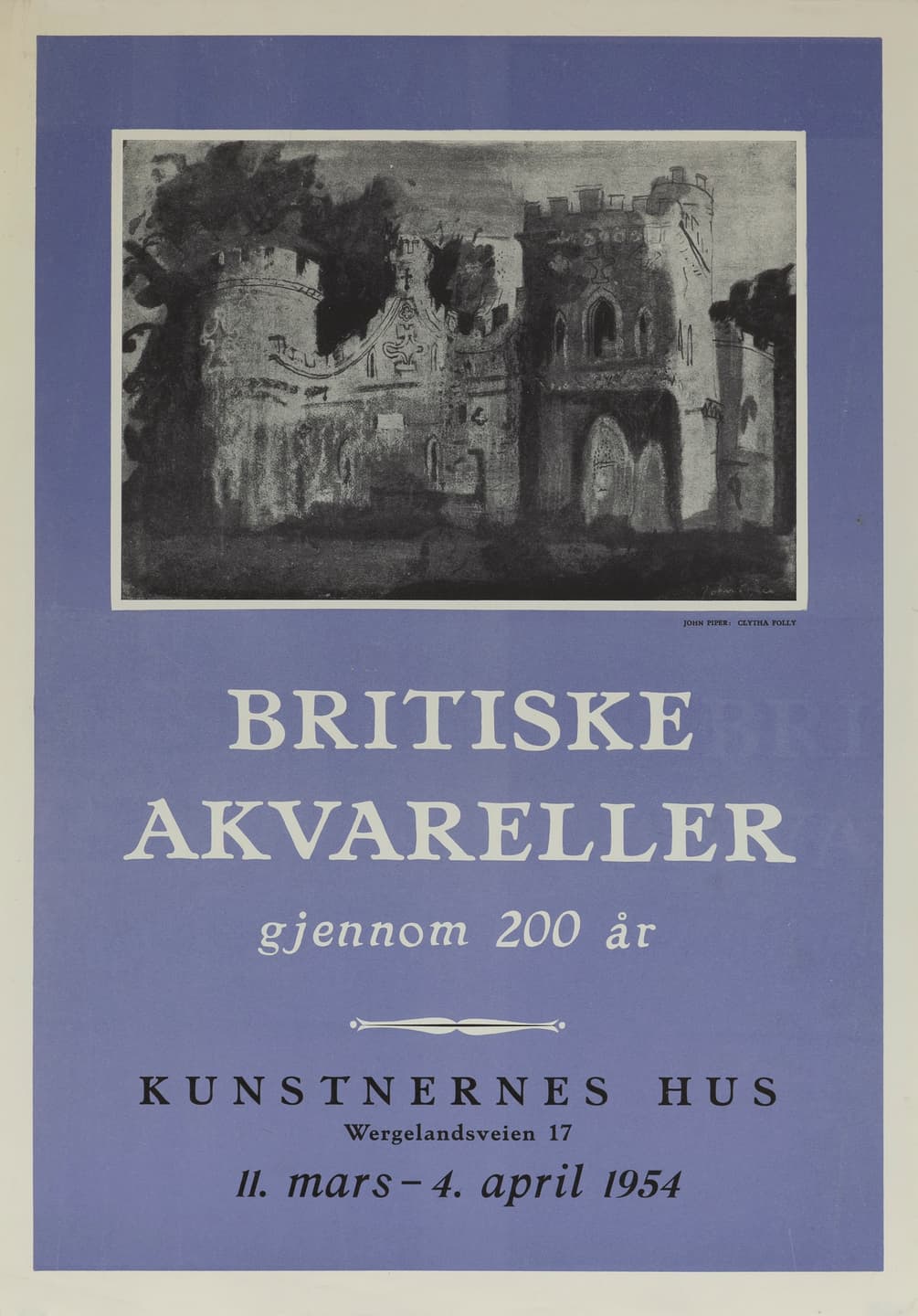

The second group has its sources of inspiration further back, in Girtin's romanticism and Cotman's formal solidity. They seek to reinforce the apparently random nature of the first group by emphasizing structure and drawing. Édward Bawdeni's "Rocca di Papa" recalls Cotman's drawings of monoliths, so massive in its design, and John Nash's "Westleton Quarry" also echoes Cotman. John Piper is more deeply indebted to Girtin, and his romantic castle is reminiscent of the latter's great work with similar motifs, no. 1, only with a slight touch of eeriness added.

The three exceptions, those who stand outside these directions, are Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, who add a new plasticity to watercolour, originating in their sculpture — and Augustus John, our greatest living portrait painter and draughtsman. His finest works were made before 1920 and his varied wealth of lines is well illustrated in "Group of Irish Gypsies" made around 1917.

It is also interesting to note how many English artists have worked in other countries. Almost all 18th century watercolorists went to Italy and Switzerland. Lear who is perhaps better known as a writer of comic verse traveled throughout the Middle East and to India, Holland went to Portugal and Venice, Roberts and Lewis to Palestine, Syria and Spain, Callow and Cox to France. Cotman went three times to Normandy to make sketches, and his vivid "Chateau Navarre" painted c. 1823 shows how preoccupied he has been with this new landscape. And Girtin went to Paris where, in the last year of his life, he made the charming little watercolor of the "Louvre". In our time, the artists travel as much as they can despite the currency obstacles. We show two landscapes from Norway, which John Minton made during a recent visit here.

Nevertheless, of course, English artists throughout the ages have been primarily inspired by the refined beauty of the English landscape and by the soft English light. No other medium of expression can capture these values better than a watercolor lens.