Going East on Michigan Avenue from Westland to Downtown Detroit

Lørdag 19.11.22

Velkommen til visning av Going East på Michigan Avenue fra Westland til Downtown Detroit, presentert i forbindelse med utstillingen Mike Kelley: Kandors på Peder Lund (19. november 2022 - 4. februar 2023). Utstillingen markerer den første solopresentasjonen av kunstneren i Norge.

En introduksjon til filmen vil bli gitt av Mary Clare Stevens, presidenten for Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts.

Artist's statement

Mobile Homestead is a public sculpture conceived specifically for the Detroit area. The work was commissioned by Artangel, a London-based arts funding organization that specializes in site-specific works. Spearheaded by James Lingwood, Mobile Homestead is the first project produced by Artangel in the United States. At a certain point, Artangel partnered with the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCAD) in downtown Detroit to co-produce the work.

Mobile Homestead is a full-scale replica of the house in which I was raised (a single-story ranch-style house), which still exists in the Detroit suburb of Westland, a working-class residential neighborhood. The replica will exist permanently on a grassy lot adjacent to MOCAD, where it will function as a community gallery—in concert with various local community groups. The facade of the structure is designed to be removable and is mounted on a chassis; it is “street legal” and close in size to a traditional mobile home so that it may be driven around the Detroit area to provide various sorts of public services. It is my wish that the community gallery will not simply be an outpost of MOCAD, but that it represent the cultural interests of the community that exists in proximity to it.

A complex basement area will be built beneath the house, mirroring the floor plan of the original Kelley family home. Though the floor plan of the underground zone is the same as the house, the rooms may not be entered directly one from the other. To accomplish this architectural effect, the subground section of the house will be constructed two levels deep so that visitors must travel labyrinthian hallways and climb up and down ladders to reach the next space. The basement is being structured like this, specifically so that its floor plan is unrecognizable as the mirror of the house above. In this way, each room will take on a distinct cell-like quality. In contrast to the public orientation of the mobile section of the house and the community gallery/upper section, the lower levels are designed for private rites of an aesthetic nature. This section of the structure will be made avail-able, on occasion, to individual artists or groups of my choosing. The underground zone will not be open to the public and the works produced there would have to be presented elsewhere, or not at all.

Mobile Homestead is also intended to have a parasitic relationship with Henry Ford’s collection of structures associated with great American historical figures. Founded in 1929 by the automobile manufacturer in Dearborn, the Henry Ford Museum houses the industrialist’s vast collection of machinery and technological items, period furnishings and Americana. Linked to the museum is Greenfield Village, a sprawling outdoor theme park made up of over eighty historical buildings, including Ford’s birthplace, Thomas Edison’s laboratory, and the Wright Brothers’ workshop. The traveling portion of the house is intended to function as a somewhat ironic comment on such grandiose notions of history; it is an “every man’s” home associated with Greenfield Village simply through proximity when it is driven into the parking lot where, on occasion, I plan to have it sit as long as legally possible.

Mobile Homestead’s normal driving route would take it west down Michigan Avenue—starting at MOCAD downtown, continuing on to the “mother ship”—the original home in Westland—then heading east to Greenfield Village and back to MOCAD. As it goes it performs its social duty of useful public service, for example it could function as a blood mobile, food drop-off site, etc. The house is not intended as a monument to me or my family. It will not be designated as the “Kelley family home.” It is simply a house typical of the area where I grew up. Yet even this aspect of the project is far from neutral. A replica of a typical house of the suburbs, it will look quite out of place in downtown Detroit. This fact itself points toward the complex racial and class-based issues that are representative of the Detroit area—for example, the “white flight” from the city after the Detroit race riots of 1967, which resulted in a city with a primarily African American population surrounded by white suburbs.

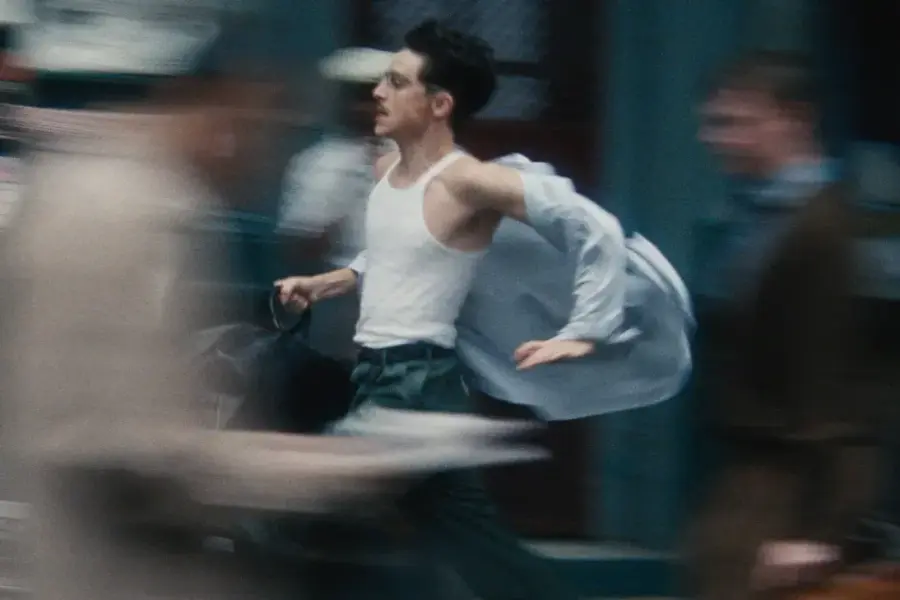

With this in mind, in 2010 I produced a video documentary that follows the route of the completed traveling section of Mobile Homestead from MOCAD’s site in downtown Detroit to Westland and back. The documentary consists of two feature-length videos: the first follows the Mobile Homestead as it heads west to the original Kelley house; the second follows the vehicle’s return east to downtown Detroit. The documentary traces a remarkable variety of urban and outlying areas, starting with the urban revitalization of the Woodward area and the urban blight that surrounds it and continuing through to the comparative wealth of Dearborn, the black slums of Inkster, and into the white working-class neighborhoods of Wayne and Westland.

A third video was made, documenting the September 25th, 2010, launch event of the mobile section that occurred on the site at MOCAD where the completed Mobile Homestead will eventually stand. It records an ode by local poet John Sinclair and the christening of the mobile section as well as the speeches delivered by local community leaders and representatives of Artangel and MOCAD. It also features an interview with the present owner of the Kelley family home and footage of a food drive that took place in the parking lot of Greenfield Village. Those attending the christening event were invited to form a caravan to follow the mobile section on its tour, during which locals were treated to a festival of live music made up of a variety of bands representing the rich cultural diversity of the Detroit area. These included soul, rock and punk, Polish polka, Irish, and Cuban bands and hip-hop deejays. Ironically, the driver of Mobile Homestead ran into the curb making the turn from Woodward onto Michigan Avenue—literally the first block of the tour. The scheduled tour was cancelled and the vehicle was not re-paired until the end of the day, at which point it was driven back onto the MOCAD site just as the music concerts were ending. This video is edited in such a way as to give the impression that the event was successful. Only, at the end, is it revealed that Mobile Homestead never actually completed its route that day.

Luckily, the video documentation of the travel route of Mobile Homestead, which was shot before the actual opening event, went far more smoothly. I had scouted the route thoroughly while in Detroit for preproduction meetings. Priority sites were chosen, camera angles were fixed, and a shooting script was drawn up. Oren Goldenberg, a local filmmaker, was hired to shoot the tour and individual sites. Scott Benzel, who works with me in my studio in Los Angeles on sound, came to manage the production. Laura Sillars, who was sent from England by Artangel to help oversee the project, was essential in organizing the interviews even though she had never been to Detroit before. She, in essence, directed this aspect of the documentary.

As Mobile Homestead travels the Michigan Avenue loop in the two feature-length documentaries, there are cutaways to various homes and businesses where interviews are conducted. As I’ve already pointed out, the communities that Mobile Homestead passed through are incredibly varied with regard to ethnicity and economic scale. Some towns, such as Dearborn—home of the Ford Motor Company—are going through major social changes. Dearborn, once an enclave of white wealth, surrounded by black poverty, has become a thriving middle-class Arab American community. Interviewees included the workers and owners of shops, bars, and restaurants, a motorcycle gang, local citizens in their homes, strip-club dancers and street prostitutes, members and officials at a variety of churches (including a priest at St. Mary’s Catholic Church and School in Wayne, which I attended as a child), social service organizations, as well as representatives of the Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, and the Ford Motor Company at its corporate headquarters.

In 2011, I was invited to present the Mobile Homestead project at the 2012 Whitney Biennial in New York. The videos documenting the mobile unit’s travel route and christening ceremony will be screened. But I consider the Mobile Homestead project to be a work in progress. The videos, on their own, do not convey the complex nature of the project as a whole, which will eventually include documentation of the exhibitions that will take place in the community gallery and the various social services that will be linked to the mobile section. Phase two of the project, the construction of the permanent structure next to MOCAD, is not yet even in production.

The Mobile Homestead project is my first sustained attempt to delve into the world of public art—something I have always shied away from in the past. I have a deep distrust of art that is foisted upon the public; I prefer that people go and see art if they choose to do so. (Of course, this stance does not apply to guerilla art—such as political protests or graffiti art, etc.—which is specifically intended to be transgressive. I mean, in this case, public art that is sanctioned by tax-payer dollars or public institutions.) This project developed in a way I would never have anticipated. Initially it was a secret project, designed for my own perverse amusement, situated in a lower-class suburb of Detroit. After this turned out to be impossible (because the current owner of the house I grew up in would not sell it to me, and because I became involved with the public institutions Artangel and later, MOCAD), I was forced to reconsider my intentions and change my approach in response to the work’s new, public nature and its shift in location. Going public led to a nightmare of complexity, not only in the production of the work but also, personally, in its very meaning for me. As public art, intended to have some sort of positive effect on the community in proximity to it, it is a total failure. Detroit is a poor city, and I don’t believe that the funding exists to organize the social programs associated with the project, or to even cover the operating costs of Mobile Homestead. The work could become just another ruin in a city full of ruins. Yet, in the beginning, I never intended the project to have any positive effect. Turning my childhood home into an “art gallery/community center” was simply a sign for social concern, performed in bad faith. The project, in its initial conception, expressed my true feelings about the milieu in which I was raised, and my belief that one always has to hide one’s true desires and beliefs behind a facade of socially acceptable lies. But, perhaps, the failure of the Mobile Homestead project now, after being filtered through the institutions of the art world and community services, is successful as a model of my own belief that public art is always doomed to failure because of its basic passive/aggressive nature. Public art is a pleasure that is forced upon a public that, in most cases, finds no pleasure in it.

Om kunstneren

Mike Kelley was born in 1954 in Detroit, Michigan, and died in 2012 in Los Angeles, California. He received his B.A. in 1976 from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his M.F.A. in 1978 from California Institute of the Arts, Valencia. Recent solo exhibitions include “Categorical Imperative and Morgue” at Van Abbemuseum, Stedelijk, The Netherlands in 2000, “Mike Kelley–The Uncanny” at The Tate Liverpool, England in 2004 (traveled to MUMOK, Museum of Modern Art, Vienna), “Profounders vertes” at Musée du Louvre, Paris (2006), “Themes and Variations from 35 Years” at The Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2012) and Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2014).

Kelley’s work belongs in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Centre Pompidou, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among others. He received the Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Arts’ award for Fine Arts in 2003.